What is the American Studio Crafts Movement?

Often when we talk about the impact and continued popularity of mid-century furniture, the words Studio Crafts sneak into the conversation. Many items from the American Studio Crafts movement come up in routine personal property appraisals conducted by The Appraisal Group – yet many people I speak with draw a blank. Today I’ll explain it.

After World War II, people were ready for something new. For monied families, it meant building glass International Style homes. For the middle class, ranch style homes did the trick. Their ceilings tended to be low although they spread out vertically. The look of the day, low slung furniture and modernistic lighting, fit perfectly into these dwellings.

The period’s financial prosperity, especially the G.I. bill, made it possible for couples to indulge their tastes and acquire one-of-a-kind objects made in studios by artists and woodworkers. Hence the name Studio Crafts.

Although studio crafts were not limited to furniture makers, there work is most often still seen in homes today. Among the leaders were:

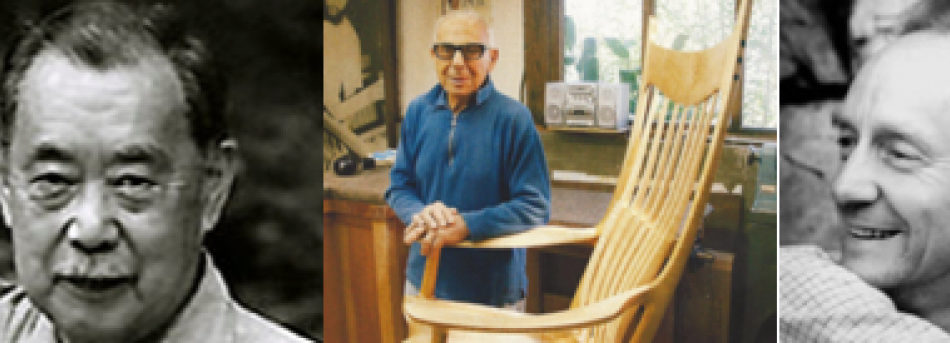

George Nakashima (1905 – June 15, 1990) was a woodworker, architect and furniture designer. Trained at MIT and well-traveled, he was relegated to Camp Minedoka in Hunt, Idaho in 1942, when so many Japanese-Americans were interred. In 1943, Antonin Raymond successfully sponsored Nakashima’s release and invited him to his farm in New Hope, Pennsylvania. In his studio and workshop at New Hope, Nakashima explored the expressiveness of wood by choosing boards with knots and burls and figured grain. He designed furniture lines for Knoll, Widdicomb-Mueller as he continued his private commissions. The studio grew incrementally until Nelson Rockefeller commissioned 200 pieces for his house in Pocantico Hills, New York, in 1973.

Wharton Esherick (1887 – 1970) was a sculptor who worked primarily in wood, applying the principles of sculpture to utilitarian objects. The American Arts and Crafts style influenced Esherick’s early work that he decorated with carving. In the late 1920s, he abandoned carving and focused instead on the pure form of the pieces. In the 1930s. The organicism of Rudolf Steiner, as well as by German Expressionism and Cubism became later influences. The angular and prismatic forms of the latter two movements gave way to free-form curvilinear shapes. He progressed to creating interiors, the most famous being the Curtis Bok House (1935–37). Though the house was demolished, Esherick’s work was saved. The fireplace and adjacent music room doors can be seen in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the foyer stairs can be seen in the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami, Florida.

Sam Maloof (1916 – 2009), another woodworker is perhaps most famous for his chairs. They are ergonomic and austere. You can identify a Maloof chair by its rounded over corners at mortise and tenon joints, carved ridges and spines, decorative ebony dowels, dished-out seats; and clear finishes. Maloof favored black walnut, cherry, oaks, rosewood and yew. On larger pieces, he often used poplar in areas that would not be visible during ordinary use. The Smithsonian Institution called him a “America’s most renowned contemporary furniture craftsman” and People magazine dubbed him “The Hemingway of Hardwood.” But his business card always said “woodworker” – a word he found to be honest and true.

Dec 16, 2022

Dec 16, 2022